Ascendonica blog by Lenore Rouse

The source for news and information on the Rare Books and Special Collections Department of the Catholic University of America

Nel 1928 la famiglia Castelbarco-Albani mise in vendita una ricca sezione della biblioteca conservata a palazzo Albani (Urbino). A comprare i circa 10.000 volumi fu la Catholic University of America di Washington D.C., dove ancora oggi sono conservati e in parte catalogati.

Per diffondere i risultati degli studi su questa collezione la curatrice dei fondi storici della biblioteca, Lenore Rouse, ha realizzato il blogpost Ascendonica che a breve, purtroppo, non sarà più online.

Per evitare la dispersione di importanti informazioni ed anche per continuare a promuovere le ricerche e lo studio delle biblioteche Albani, abbiamo deciso di ospitare in questa pagina le note relative alla Clementine Collection (The Albani Library) già apparse in Ascendonica. Ringraziamo vivamente Lenore Rouse per la generosa disponibilità che ha sempre dimostrato nei confronti dei progetti Archivio Albani e Disiecta membra.

Clementine Collection (a.k.a. the Albani Library)

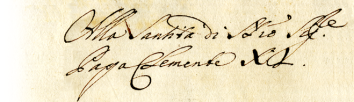

The nearly ten-thousand volume Albani Library was acquired by the Catholic University of America in 1928. The residue of the Albani family's combined Urbino and Rome libraries, this collection comprises church history, canon and Roman law, Jansenism, Italian literature and numerous presentation copies, gifts to Pope Clement XI and to his nephews. Also present are two book catalogs in manuscript, one compiled in 1701 and the other begun around 1720, which document the contents of the Urbino library near the beginning and end of Clement's pontificate. As a window into readership and collecting practices of the early 18th century, these volumes are primary sources which will be the first priority in the RBSC department's planned digitization efforts. The 1720 catalog includes a key to the in-house classification scheme used for a portion of the collection. Books were identified by paper labels pasted on the spines, which indicate press and shelf numbers in letterpress, and leave space for the book number to be added by hand. Below is the label on a volume of the Plantin Polyglot - case C, shelf I ("primo ordine"), book number 22 lettered within the trimount, a component of the Albani coat of arms.

Form as well as content make this a collection of bibliographic interest. Most of the volumes are in their original bindings, generally simple vellum or tacketed bindings, but with a substantial number of elaborate gilt goatskin examples, especially among the presentation copies. Many of the latter are armorial bindings, with the coats of arms of various members of the Albani family or of ranking ecclesiastics of the period. In another category are the delicate paper covers formed of ornate and colorful "Dutch gilt" paper, a sample of which is shown at the top of this page.

With the exception of a handful of titles, the volumes in the Clementine Collection are uncataloged, and the Catholic University’s copies are not reflected in WorldCat. Furthermore, some 30% of the titles in this collection are unique and unrepresented either in WorldCat or in European libraries. We estimate that some 2000 volumes are 16th-century imprints, which, when cataloged, will double RBSC’s holdings of such volumes. The importance of bringing to light these works for students and researchers impels the small staff of RBSC to embark on what will doubtless prove a lengthy process of cataloging the Clementine. We plan to use the Ascendonica blog to showcase the discoveries made in the Clementine Collection as we bring this “Archivio Segreto” into the light of the 21st century.

Small details

“Much scholarship depends on devoting a disproportionate amount of attention to relatively small details” -- James Thorpe, Principles of textual criticism.

In most library cataloging, even with the exacting standards applied to rare books, the small details which may provide grist for a scholar's mill are often omitted from bibliographic descriptions, either for reasons of economy or through the cataloger's non-comprehension of unfamiliar or even perfectly baffling elements. Further, it is currently thought that the recording of details is unnecessary, given the certainty that every page of a book will soon be digitally captured, allowing a scholar to see at a glance those unique features which might require hours of painstaking work for a librarian to describe in words.

In the vast majority of library cataloging records, physical features of a book have usually been overlooked, with stress laid on the information needed for retrieval of a given text. Only in the last three decades have rare book catalogers begun to develop protocols for recording and making retrievable the physical features of books, most notably with the RBMS Thesauri of ALA's Rare Book & Manuscript Section. Provision is now made for recording binding characteristics, former owners' names, and other visible features of a book. But even so, some elements such as marginalia, dog-earing, shelf-marks, and other evidences of provenance may not make the cut. Sometimes these features elucidate the book’s history but just as often they are difficult to describe and may raise more questions than they answer, leading the cataloger on an exciting if time-consuming chase after names, literary allusions, and mystifying abbreviations, all of which might be evidence of some sort for scholarship of some kind, but probably a kind unrelated to the text of the book.

De Partibus Aedium

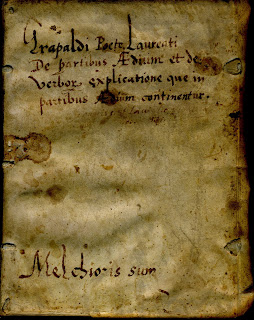

A case in point is this recently cataloged volume from the Clementine Library.

Unprepossessing in appearance, this book on architectural terminology has been personalized in a variety of ways. The title is scrawled on the cover: Francesco Mario Grapaldi’s De Partibus Aedium (Parma, 1516). The cover also bears, in the same hand, the engaging announcement of ownership: “Melchioris sum” or “I belong to Melchior.”

Goodbye Cruel World

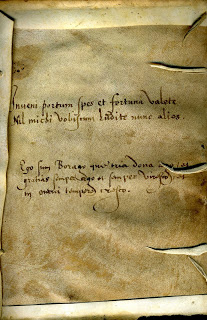

Even more interesting are the two unrelated verse quotations written inside the vellum cover. The first verse reads "Inveni portum spes et fortuna valete / Nil michi vobiscum ludite nunc alios", roughly translated, "I have reached the harbor; farewell Hope and Fortune. To me you mean nothing; now go make sport of others."

The lines are a Latin translation of one of the most famous epigrams (in this case really an epitaph) from the Anthologia Graeca or Greek Anthology. Books have been written on the Anthologia, which occupies five volumes of the Loeb Classics. Once better known than at present, the Anthologia was an important source in European literature from the Renaissance through the nineteenth century. Notable translations into Latin included that by the Dutch legal scholar Hugo Grotius and portions of the Anthologia were translated or mined by other famous literary figures, including Erasmus and Thomas More. In 1518 when the second edition of More’s Utopia was printed in Basel, the volume included the first printing of More's Latin Epigrammata along with a preliminary section of Progymnasmata, containing verses by More and his friend, the grammarian and Greek scholar William Lily (1468-1522). Progymnasmata 6 includes both More's and Lily's Latin renderings of the Greek epigram on Fortune. However it is not the translation by More which was copied into our binding, but word for word the text by Lily, varying only in the medieval spelling michi rather than the classical mihi. It would be interesting to know for certain the source for the manuscript lines, to learn whether the owner of the 1516 Grapaldi book copied into it the published epigram two years later, or whether he relied on a different unknown source.

I am Borage

The second verse is more difficult to decipher but seems to read: “Ego sum Borago qui[?] tria dona ago / et gratias semper ago et semper viresco, et in omni tempore cresco." ("I am Borage who brings three benefits: I always bring good cheer, I'm always green, and grow in every season.") This little Latin jingle seems to be a fairly accurate description of the herb borage (Borago officinalis), a common blue-flowered plant which grows around the Mediterranean, in Europe and in other temperate climates. The leaves are used in salads and the flowers are among the few naturally-occurring blue species which are not poisonous to humans. Used as a summer spice for wine, borage has been reputed to have mood-elevating properties, and indeed the most common variant of the poem "Ego Borago gaudium semper ago" reflects this belief, as do several vernacular texts. The plant's extracts, now marketed in health food stores, are used to treat arthritis and hot-flashes, and borage is a favorite "companion" plant of gardeners, requiring little maintenance. After five-hundred years the Latin doggerel penned in the old binding is still relevant, and possibly the writer felt it to be a cheerful counterpoint to the epitaph he had written above it. In any case, no researcher looking either for the epitaph or the homage to borage would think to find it by searching for a book on architecture.

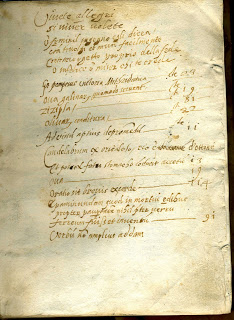

On the endpaper opposite these verses are later and more extensive manuscript notations, beginning with six lines of Italian verse and continuing with citations to various topics within Grapaldi's architectural treatise, noting relevant page numbers.

An educated guess places these lines in the period of Albani ownership of the book, and they remain the subject of further investigation.

But a mysterious abbreviated note at the very end of the book on the lower pastedown (which, like the upper, was never actually pasted) seems to be in an earlier (16th century?) hand and is rather more interesting. What does it mean? It may be a date, 5 July. "Completed Jul. 5" perhaps? On close inspection it has the appearance of two pens at work, a light ink with a darker heavier hand superimposed. In any case the presence of the neatly cut out window on the leaf preceding it adds to the mystery. Normally one sees cut-outs of this sort when a signature is clipped from a leaf. But this missing corner seems somehow related to the notation on the next leaf. Perhaps a pattern like this is known in other books, but it is not easy to alert scholars to the presence of such an anomaly, either in a verbal catalog description, or by digital means.

New Albani manuscripts on Vatican Library website

Recently launched by the Archivio Albani is a collaborative project Disiecta membra: tracing the history of the Albani Libraries. This endeavor is supported by the Biblioteca e Musei Oliveriani and, by the ongoing support of Count Clement Castelbarco Albani to the operations of the Archivio Albani. CUA's Rare Books and Special Collections department hopes to contribute in a small way to this exciting initiative. As the locus of the largest surviving collection of Albani books, chiefly from the Urbino library, the department has been involved with the study of Albani provenance questions for at least 6 decades and holds in the collection several manuscript catalogs describing the contents of the Urbino library.

Crucial to any study of the Albani libraries, scattered by wars, looting and auctions, are three important manuscript catalogs owned by the Vatican Library, recently digitized, and now publicly available on their website. By entering the shelf mark number in the search box, researchers may retrieve Vat. lat. 10476, 10477 or 10485. These manuscripts, (mentioned by Bernard Peebles in his 1961 article The "Bibliotheca Albana Urbinas" as represented in the Library of the Catholic University of America) have long been considered invaluable to scholars doing research on the Albani books located at Catholic University. The splendid digital images of the Vatican volumes already reveal binding characteristics very similar to books held at CUA, and access to the contents of these catalogs will undoubtedly shed light on some of the material here in Washington and its complicated provenance.

We are grateful to Dr. Paolo Vian, Director of the Manuscript Department of the Vatican Library for expediting the digitization of these volumes, as well as to Dr. Brunella Paolini (Biblioteca Oliveriana) and Dr. Antonio Becchi (Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte) for their hard work in this and other aspects of the Disiecta membra project.